There’s something about Sasquatches and Yetis that makes certain authors and auteurs want to turn them into Giant Furry Friends. Maybe it’s the inherent coolness of the beast. He is usually huge, and he’s canonically stinky, and he’s extremely hairy. And yet, cleaned up and set in a fantasy world, he is just about irresistible.

Robinson’s almost-but-not-quite-real Nepal of the late Eighties would not be half as cool a place without its population of yeti. The collection of novellas published as a novel under the title of its first section, Escape from Kathmandu, is a lighthearted but subversively serious look at the community of Western expats on the roof of the world. Protagonists George and Freds join a shifting (and sometimes shifty) cast of characters to explore wonders both real and mythical, from the true nature of Shambhala to the real-life weirdness of the Nepali government. In among all the adventures and the capers, they contend with real-world problems: poverty, politics, exploitation of land and people and resources, ecological destruction.

They first meet through a slight criminal act on George’s part. George owns a company that runs treks into the mountains, including Everest. At one point, when he’s in between gigs in Kathmandu, he raids the dead-mail rack at the Hotel Star, and appropriates an unusually thick packet. It’s addressed to a person whose nickname is Freds, from a zoologist turned trekker guide named Nathan. Nathan helped organize a scientific expedition into the Himalayas, officially to set up camp along the treeline and study the wildlife, from insects and birds on up. But as he quickly reveals in his long letter, there’s another mission, and Nathan just happens to have fulfilled it.

Inadvertently and accidentally, and incredibly, Nathan has met a yeti. He can’t tell anybody about this, but he’s just about to explode with the strain of keeping the secret. Therefore he’s sharing it with his old college roommate Freds.

Nathan had been helping ornithologist Sarah with her research on the honey warbler. Nathan has a terrible crush on Sarah, but Sarah’s boyfriend Phil is the expedition leader. Also, an asshole, but Nathan is honorable and tries not to poach.

One day when Nathan is sitting alone at the pool where they found the warblers, he finds that he’s being watched by a pair of human-like eyes in a bearded face. It’s about to become clear that mammalogist Phil is searching for the yeti—and Nathan has found him. Or he’s found Nathan. It’s not completely clear which.

That night in camp, the members of the expedition start talking about the yeti. They’re all speculating about what would happen if they found actual physical evidence. And better yet, says Phil, finally showing his hand, if they captured a live one.

Nathan can’t help himself. He declares that if they did find one, they should let it go and never tell anyone about it. If the world knew that this creature exists, this part of it would be inundated with hunters and tourists and scientists. The ecology would be ruined. The yeti would become a scientific specimen, a zoo animal. He needs to stay unknown and officially undiscovered, for his own sake and for the sake of his habitat.

The other scientists beg to differ. Except Sarah: she gets it. The rest are all about sharing scientific knowledge with humanity. It won’t do any harm to the animal. Or not much. And think of the value to Science!

Science wins out. They set up a blind and lie in wait for the yeti. The creature is nocturnal, supposedly; therefore they watch by night as well as by day. And one night, when Nathan is on duty, the yeti reappears.

He’s human-sized, which is an important detail for this particular plot. His head is oddly shaped, with a tall crest, but it’s almost human. He’s covered in dark hair, except for his face, with a protruding nose and a strong jaw. There’s a stick in his long, skinny hand, and he’s wearing a necklace of fossilized shells.

He is, Nathan concludes, some form of hominid. He carries a tool, he decorates his body. And he speaks a humming language punctuated with whistles, looking Nathan in the eye and showing clear intelligence.

Phil comes crashing in, and Nathan and the yeti flee together. When they’ve shaken off pursuit, the yeti makes Nathan a gift of his necklace, and heads back into the wilderness. Nathan is left stunned and deeply thrilled, and more determined than ever not help Phil collect this prime zoological specimen. He sabotages the camp’s access to the yeti’s range, and makes sure the expedition has to shut down.

He does it for the best of reasons. “There’s a creature up there, intelligent and full of peace. Civilization would destroy it. And that yeti who hid [from Phil] with me—somehow he knew I was on their side.”

That’s it for the letter, but not for Nathan or Freds or, as it turns out, George. Nathan shows up in the Hotel Star, looking for his letter. He can’t find it because George stole it, but George never actually confesses. What he does instead is help Nathan find Freds, and end up joining them in a rescue mission.

Phil and Sarah and company came back with a rich American, a big-game hunter, who bankrolled a new expedition. The expedition has returned from the mountains to Kathmandu, and they’re holding something or someone prisoner at the Sheraton. Nathan and Freds, not to mention George, can well imagine what it is. Phil has captured a yeti.

Their response is immediate and inevitable. They mount an expedition of their own to rescue the yeti and return him to his home. It’s as wacky a caper as you might imagine, complete with wild disguises, clever subterfuges, a bicycle chase (with echoes of the iconic chase in ET), and a Famous Celebrity Walk-On: none other than Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter.

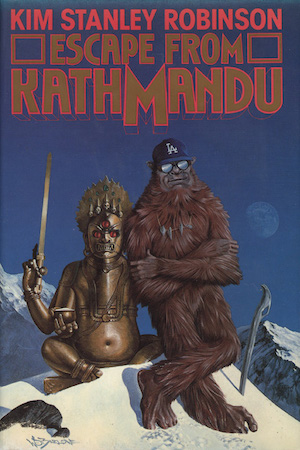

The yeti turns out to be the one Nathan met by the pool on the earlier expedition. He’s small enough and intelligent enough to wear human clothes and impersonate a hirsute, mostly inarticulate person with the monumental calm of an enlightened sage. For this, George et al. (including Sarah, who finally dumps Phil and hooks up with Nathan) call him Buddha.

George isn’t sure if Buddha is typical of his species, or if he’s possibly mentally ill. These days George might wonder if Buddha is, by yeti standards, neurodivergent. He doesn’t appear to have resisted capture, and he’s content to be rescued. He’s a deeply mellow, calm, unflappable person who goes where he’s directed and does what he’s asked to do.

When he’s finally home, George makes him a gift of the Dodgers cap that concealed his oddly shaped head. In return, he breaks up the necklace he gave Nathan, that Nathan tries to give back to him, and gives each of his rescuers one of the shells that had been strung on it. He even offers a human word: “Namaste.”

Buy the Book

Escape From Kathmandu

That’s the end of Buddha’s arc in the novel/story collection, but he has a cameo later, in The True Nature of Shangri-La. Freds pulls George back into his chaotic life, in an attempt to keep the government from building a road to the hidden village of Shambhala. This is the true Shangri-La, the mystical monastery ruled by an ancient reincarnated lama. It lies deep in the mountains, in the land of the yeti.

When it comes time to defend the town, the human forces are joined by a contingent of yeti. Among them, George sees one in a Dodgers cap. It’s a nice moment, and a good feeling, to know that Buddha still cherishes the gift George gave him.

The yeti of Robinson’s Nepal is an enlightened being, a creature of peace. He’s an image of humanity before the Fall, and he lives in a pristine part of the world. He’s an ally of the monks and the people of Shambhala; in many ways he’s the embodiment of the Buddhist ideal.

I find myself wondering if the monks learned at least some of their practices from the yeti. If he’s a hominid, after all, it’s likely he comes from a very old lineage, even if he isn’t an actual human ancestor. The necklace he shares with Nathan and George and Sarah seems to represent his own antiquity as a subspecies: he’s as much a fossil as the shells he wears.

One of my all time favorites